The Power of Narratives in Driving Innovation

A few years ago I was at a dinner party sitting next to someone I’d just met. We began to exchange the typical pleasantries. What’s your name? How do you know so-and-so? What sort of work do you do?

Graphic by Timo Elliot, 2016

He told me he was a carpenter, and I told him I study innovation and entrepreneurship.

At this point his demeanour changed.

“Oh…innovation…”

He looked sceptical.

“So what do you think of the government’s new innovation agenda, this so-called ‘ideas boom’...”

His tone left little doubt about what he thought of it.

This was several years and three Australian Prime Ministers back, when then PM Malcom Turnbull had just launched a $1 billion national science and innovation agenda, before his party deposed him and barely mentioned the word innovation again.

Two thoughts came to mind, and I honestly wasn’t quite sure how to respond.

First, innovation is among the most important things we humans do. Our civilisation is really an assemblage of past innovations that we now take for granted. This is not only true for new technologies like fire, the wheel, electricity and the internet, but also institutional and social processes like art, religions, constitutional law and democracy. Innovation has underpinned the great enrichment that has raised the living standards of billions of people over the past 200 years. The share of humanity living in extreme poverty fell from 90% in 1820 to less than 10% today (the World Bank has a real time monitor you can watch here). Most of us likely wouldn’t be alive today if it weren’t for the efforts of past innovators (think food, heat, shelter, light, toilets and basically anything else that keeps you from dying or subsisting in misery).

Second, innovation is among the most disruptive things we humans do. Innovation fundamentally rearranges how we work, live and play. It opens new opportunities, but also displaces incumbents. It creates new winners but also new losers - at least in the short term. This is why Schumpeter described innovation as creative destruction. Creativity comes with collateral damage. Moreover, the gains from innovation can be distributed wildly asymmetrically at first, both inside organisations and in society at large. So reflexive concern about the impact of innovation is understandable.

In business, the word innovation is constantly thrown around, but rarely defined let alone approached thoughtfully and systematically. Workers are urged to be more innovative one minute but then see every attempt to try something new blocked the next. This is part of the reason Wired magazine once called innovation the most important and overused word in America.

These factors can mean that merely mentioning the word innovation triggers the kind of eye rolls and resistance that my new friend was sharing.

And I understand the scepticism. He didn’t feel he had a stake in the success of the ideas boom, likely assumed innovation meant a small cohort would reap outsized rewards while leaving the rest further behind.

It’s true that not everything that carries the name innovation benefits the common good. But growing and sustaining the common good absolutely depends on continuing to drive innovation in business and society. Most things we care about - food and energy production, transport and building materials, healthcare and education will fundamentally depend on innovation over the coming decades to address these grand challenges. The fact that people vastly underestimate how much innovation has improved human living standards suggests a failure in the way we commonly talk about it.

Both in society and inside organisations, narratives matter. While this has long been recognised in fields like history and anthropology, now even mainstream economists are now starting to highlight the importance of narratives in driving major events. The short-lived Australian ideas boom was an example of a failure of innovation narrative at the societal level. But research demonstrates that organisations also frequently fail in constructing an innovation narrative that helps them succeed.

How innovation narratives work

Caroline Bartel and Raghu Garud, in a landmark paper on this topic, proposed that innovation narratives are effective when they function as ‘boundary objects’ around which different groups can coordinate meaning and actions. Narratives offer the connective thread between the past and future during moments of uncertainty, they help people understand what they are doing and why.

Bartel and Garud argue good innovation narratives help to:

Motivate people to recombine different ideas to generate novelty.

Promote real-time problem solving that promotes commercial development.

Sustain innovation efforts by linking present challenges with past experiences and future aspirations.

But where do you start with an innovation narrative? And how do they interact with concrete innovation initiatives?

Developing a growth-enabling innovation narrative

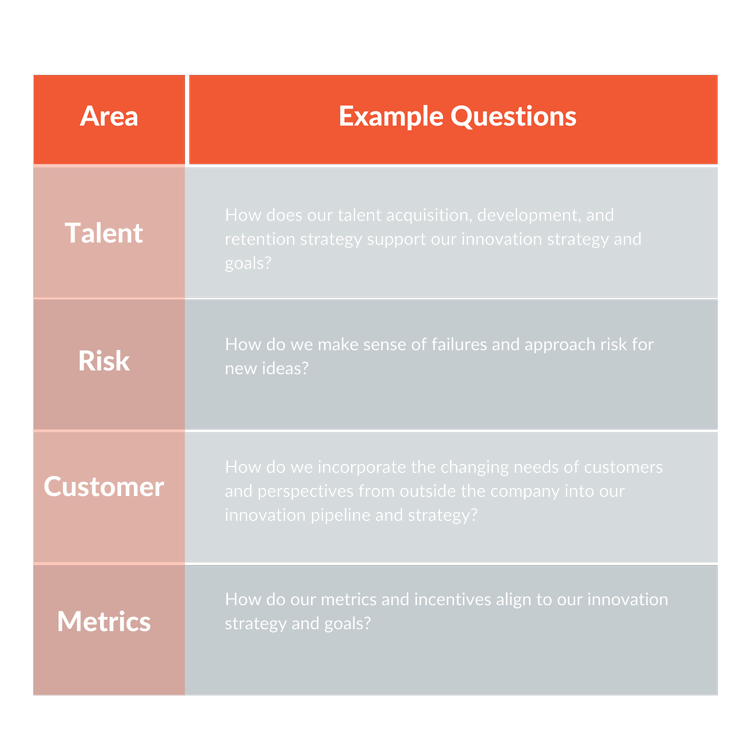

George Day and Gregory Shea argue that growth-enabling innovation narratives are crucial to sustained innovation performance and commercial success. Just like the case of Whirlpool, growth-enabling narratives must support clear strategic goals, but also support employees with a sense that these targets are achievable and supported (rather than disabled) by the organisational system. They offer some practical advice for leaders seeking to understand the present state of organisation and potentially craft a more constructive and growth directed innovation narrative.

First, they suggest listening to the way innovation and company growth is discussed by the executive. They suggest asking the executive team how confident they are that the company’s current growth goals can be achieved and why. They also suggest asking about the reasons for past success or failures with past growth goals and innovation initiatives

Next, they suggest carefully classifying the underlying beliefs that the responses convey according to the following criteria:

· Discouraging/Defensive: These responses tend to make excuses for not meeting past goals and locate the reasons for poor performance outside of the control of the team or organisation. These narratives tend to undermine innovation performance and growth.

· Optimistic/Responsible: These responses acknowledge responsibility for missing previous targets and can offer changes that have been made to improve performance. These narratives support innovation performance and growth.

· Ambitious/Constructive: These responses describe a clear growth strategy, offer lessons learned from past failures and express enthusiasm about building a new business. These narratives are exhibited by industry leaders.

Finally, if part of the problem appears to be a growth-disabling narrative, they suggest spending time crafting a more constructive, growth-enabling narrative before simply launching more innovation initiatives. This begins with envisioning a future state and story through which the company becomes an industry leader through innovation-driven growth. The next step is to render the story more concrete through articulating the sorts of behaviours and organisational culture that would enable the preferred narrative to take form.

The goal is to bring words and actions into alignment. We all know that simply telling a grand story about risk-appetite, customer-centricity or innovation without leaders exhibiting these behaviours, committing resources and designing the organisational system to support them will be ineffective (and probably counterproductive). But the work of Bartel, Garud, Day and Shea also suggest that simply launching innovation initiatives that are not underpinned by a coherent, growth-affirming innovation narrative will be just as unlikely to succeed.

Whether in society at large or inside a company, the narratives through which innovation is understood and discussed really does affect innovation performance. This is because the stories we habitually repeat shape the sense of what’s possible, and thus guide the interventions into either reproducing or changing that perceived reality.

So the next time you hear the word innovation, listen to the way it’s discussed. How would classify the underlying beliefs being conveyed – growth affirming or growth-denying? Remember that how we talk can change the way we work, and that innovation narratives really do matter.